They began wheeling me to the OR right around 2am. My mom and my cousin were walking down with us. My dad was on a flight back to Philadelphia. Everybody had been notified of the news. I was ready. I think.

My mom kissed my forehead. We all hugged. And then I blurted out the million dollar question, “Mom, what if I die?”

And then she replied with the same thing that she had been saying for weeks.

“If you had to die, you would have died already. You tried dying so many times already and you didn’t. You have a lot of things left to do in this world. You aren’t going to die.”

I’m not particularly spiritual, but in that moment, it was such a perfect thing to hear. Moms really are the best.

The OR was so bright. I hadn’t been in one of these rooms since my General Surgery rotation in medical school. And this one was top-notch. Huge. Probably the size of my whole apartment. There were at least two large HD screens staring at me. Everything was white, blue, sterile. Cold. Fascinating. I saw a generic OR checklist up on a screen, and my name was written somewhere already.

The technicians were getting some things together. The nurses began asking me some basic questions about my birth date, my allergies, etc. I don’t know if it was because my voice cracked, or because I was unusually quiet, but I think everyone around me knew how nervous I really was.

They tried to make me laugh by saying things like, “You’re gonna be famous after this, girl.”

I reacted with sarcasm, of course. I think I asked them to try not to kill me.

“We know what we’re doing. This isn’t our first rodeo,” they replied. We laughed some more.

The attending Anesthesiologist came in to help with the placement of my (millionth) arterial line.

“You know, these don’t hurt as much as I thought they would. I don’t feel a thing. I actually feel great,” I told him.

“That’s because of the Versed we just gave you.”

I chuckled.

“You ready? We gotta get you back to saving lives,” someone else said. I smiled. Yeah, I guess I did have to go back to saving lives. That made me feel better. Just a little tiny hurdle, a speedbump if anything. You’re going back to work in a few months. This is nothing.

There were a few people coming in and out of the room— making me smile, shaking my hand, giving me high fives. The CT Surgery fellow came in and asked if I had any last minute questions.

“Can you get rid of my uterus while you’re in there? Just take that thing OUT!” I asked him.

“We really only deal with the chest … but we’ll see what we can do,” he replied, with a smile.

Someone asked me what kind of music I wanted to listen to.

There was no question about it. The man who had gotten me through all of my life’s struggles. Always do your best, don't let the pressure make you panic and when you get straaaanded and things don't go the way you plaaaanned it…

“Tupac.”

And then they actually put on Tupac radio! I felt at ease. I felt good (again, might have been the Versed…).

I heard one of the nurses say that the “heart was good to go” (I didn’t know this, but apparently the surgeons have to do one last visual check on the donated organ after it has been procured and tested extensively). They had just finished examining it, and the attending was preparing to start the surgery. “They'll all be in here soon, okay? We’re gonna finish getting you ready.”

The attending and the fellow are probably changing into their scrubs, tying their caps. They're in the locker room, probably talking about how the Sixers have been doing. There’s a medical student reviewing the nerves and vessels around the heart; she knows that she'll be pimped on them. She’s nervous because this is her first open-heart case. There’s a resident running towards the OR while inhaling a protein shake because he hasn’t eaten anything in several hours. My case woke him up from sleep. I’m sorry about that; I know how much you hate cases in the middle of the night.

Alin, this is nothing for them. It’s second nature. One beautiful incision after the other. Their well-trained, delicate hands know the ins and outs of open-heart surgery. They check off each action, one by one, in their brilliant minds. Cut here. Snip there. Be careful of the recurrent laryngeal. Remove heart.

Take my heart out.

…

No. You know what? Violently rip my heart out of its cage! Get rid of it. This stupid heart that put me here in the first place. I was proud of you at first for living so long, but now I’m angry with you for dying so early. My life had been going so well. So well. I had worked so hard. I rarely complained. I was a good person for the most part. I did nothing to deserve this. Here I am now, all alone on this cold metal slab, just patiently waiting for the most frightening moment of my life. You’re barely working. You’ve decided to be difficult. You’ve made everybody put their lives aside to worry about me. I hope you’re happy.

I had a love-hate relationship with my old heart, but I spoke to it often. I was very open with it. (And, in case you’re wondering, I can say the same thing about most of my human relationships. Sigh.)

I felt it, though-- I was getting more anxious. Angry. Sad. Self-pity at its finest.

“Can I just talk to my mom one more time?"

“Absolutely. Here, call her,” said my nurse. She handed me a phone.

I called my mom and I told her that they were about to start. People were setting up around me. There was music playing. Things were getting blurry. I think the medications were kicking in because I started tearing up. I felt really warm.

“Mom, I’m not going to die during surgery, right?”

“You’re not. What do I keep telling you!"

“But remember, this is risky open-heart surgery.”

“But remember, you have so much left to do in this world."

I remember nothing else, other than a very distinct and overwhelming feeling of peacefulness (but again, that might have been the Versed…).

I understand the basics of Critical Care Medicine. I read the literature when I can. I know that less sedation and early mobility have the best outcomes for our intubated patients. Blah blah blah.

“Can we just decrease their sedation? See how they do? Let’s get them off the vent by tomorrow?” I recalled asking an ICU nurse many-a-times in my career.

Oh but I am so sorry for all of the times that I’ve done that. So, so sorry. I want my patients to do well, but I never knew how uncomfortable that breathing tube was. I would be called to go back into their hospital rooms because they were becoming agitated. “SIR, I KNOW ITS UNCOMFORTABLE! BUT JUST WAIT A FEW MINUTES! PLEASE!”

But no. No no. I didn’t know how uncomfortable it was. Now I do.

Here we were again. Me vs. The Vent. I gagged on my own secretions, and tried to grab the Yankauer suction handle. F&#%! I’m in restraints again!!! I think I was trying to scream. There were a few people around me. My nurse walked in, surprised. “It’s okay! We’ll see if we can get that out soon? I’ll be back.”

A respiratory technician came in and I kept pointing to the tube in my mouth. I started crying. Pure agony, I promise. Please someone help me, I just want this thing out.

My nurse came back in with some paper and a pen.

Any complications?

Increase fentanyl or propofol?

Increase propofol?

EXTUBATE?

I felt like nobody was listening to me. Or reading me, or whatever. And then the attending walked in. “Hey Alin, I’ll be the attending doc for the night, okay? So we were going to extubate you in the morning, but if you're comfortable with it, we will do an SBT, get another gas, and go from there.”

Oh, cool. He knew that I was a doctor. I liked that doctor talk. I gave him my restrained thumbs up, miserably losing my battle with The Vent in tears, while coughing up all sorts of secretions. My lips were dry and bleeding. There was sputum just slowly dripping down my chin and onto my gown. It was probably the most pathetic moment of my life. Those poor restrained thumbs up…..

(I laugh about it when I look back. Why? I came to find out later that the intensivist on call during those nights was someone who I had looked up to for years— one of the reasons why I was even going to do an ICU fellowship. I knew about his work since medical school, and wanted to be just like him “when I grew up.” Funny, right? So imagine drooling in front of your role model— just a humble, world-renowned ED/Critical Care physician, no big deal— who you’ve been excited to meet for years. Yep.)

He said that he’d be back in a few minutes, and the respiratory technician came back in.

“We are just waiting on the blood gas results, okay, dear? I know it’s uncomfortable. I’m so sorry. Just a few more minutes.”

I tried to glance at my ventilator settings. I passed the SBT. Please. WHAT DO YOU NEED AN ABG FOR!

Honestly, I don’t even think that I realized that I had just had heart transplant surgery. I couldn’t think of anything except getting that tube out.

The respiratory tech started setting up another oxygen machine (something we do when we extubate people instead of letting them breathe on room air right afterwards). And then, she pulled out the tube. And I took my first breath as Post-Transplant Alin.

I felt wonderful.

I was so excited. My family was standing around me. They were clapping. I tried to feel for my own radial pulse. Top-notch! Bounding. Surreal. Beautiful.

I took a look at all of the new fun medications that I was on.

Insulin drip? What the hell? Why do I have these wires coming out? What even is THAT wire? Do I have TWO central lines? What does that machine do? Is this a pacemaker? Why do I have a pacemaker?

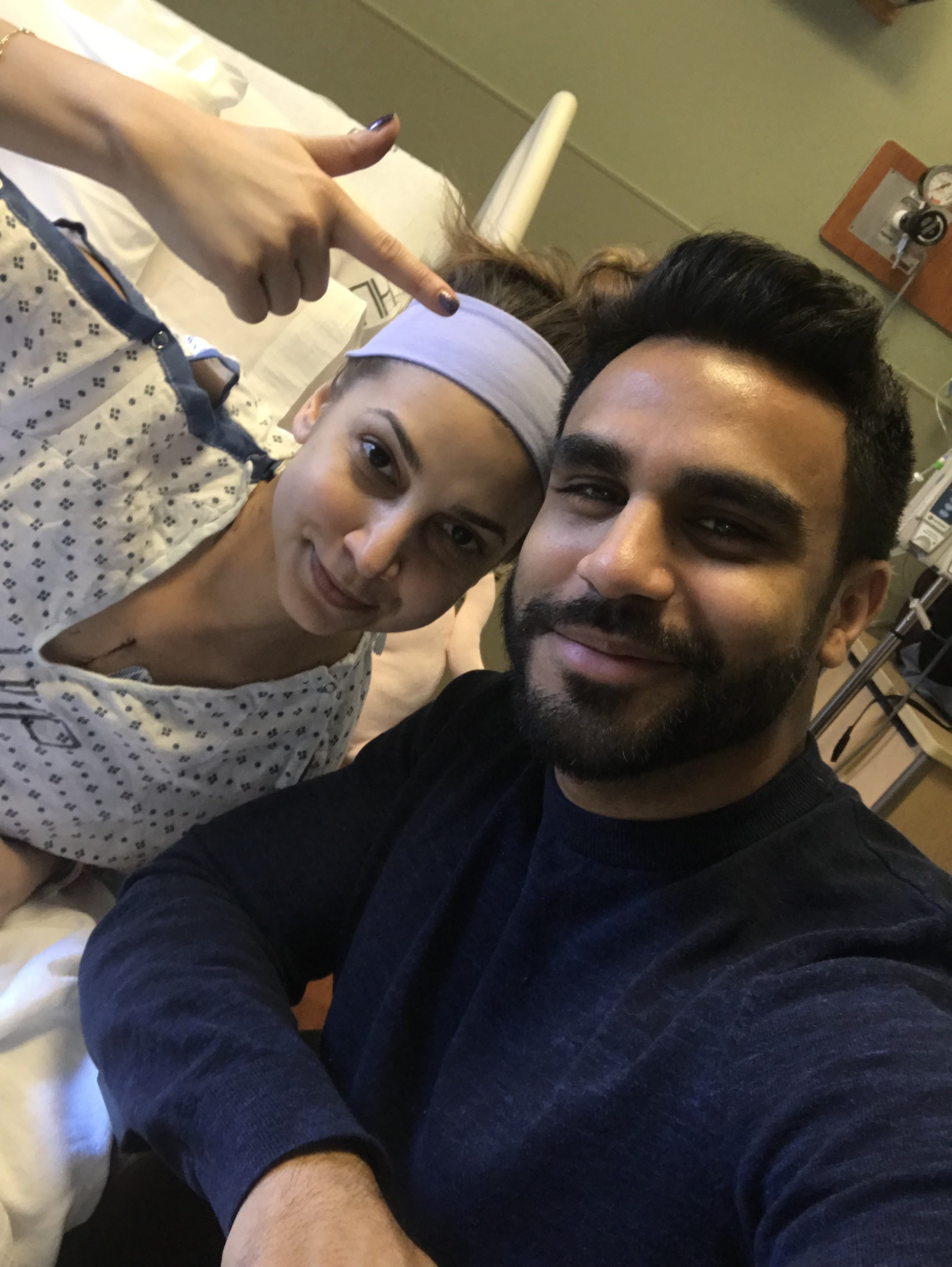

I lifted up my gown (I had no shame, ever). Woah, look at all of these surgical chest tubes! I looked at Matt and pointed to the chamber. I wanted to see how much I was draining.

I was The Quintessential ICU Patient. Post-Op. In the CTICU. Lines, tubes, and wires everywhere. Dressings on top of dressings covering I-don’t-even-know-whats. My hair was a complete mess. My whole body was orange (from prepping me for surgery). I looked like a puffy, orange (but smiling) blowfish with wires coming out of every orifice. A child’s 5th grade science project.

Or, as my best friend (who is not in medicine), put so eloquently: “You look like an outlet.”

I guess most people wouldn’t be that excited, but when you’re almost an intensivist-in-training and also critically ill in the ICU, you may just look at these things in a different light.

And I guess that was the lesson of the day, confirmed over and over again throughout my struggles earlier this year. Your psyche, your perspective really do go far when it comes to life’s hardships.

What do I mean?

Thanks to my mom, I calmed down about the surgery. She helped me realize that I was strong. It became nothing that I couldn’t handle.

While I was in the OR, I was surrounded by lovely people who reminded me that they do this all of the time. I talked myself into the fact that it wasn’t a big deal— I literally knew what they were going to be doing. It became no big deal.

After the surgery, I didn’t see my lines and tubes as painful torture devices that were there to just irritate me or perhaps leave awful scars. Instead, I saw them as incredible pieces of medical technology, each playing a major role in my healing (and some even keeping me alive). They reminded me of the reason why I had gone into medicine in the first place— why I was especially fascinated with Emergency Medicine & Critical Care: to help the sickest patients who needed the most support. I wanted to make sure that our fierce, determined attitudes and excellent resuscitation skills helped save not only their lives, but their souls. I wanted to remind them that there is so much hope and potential left, even after dancing with death and slowly sinking into the worst moments of their lives.

Sure, I was in pain, but I was lucky. It was such a humbling moment. The most humbling moment of my life.

And here is where I’ll say it: It was an honor to be in my patients’ shoes.

I’d be able to laugh and cry with them. I’d be able to physically feel their pain, their anxieties. I’d be able to read their minds— all of their thoughts about death and if their lives had any meaning at all, if they had truly lived it well. I’d know that their dignity meant everything to them. I’d know that their insomnia only came from every single one of their life’s regrets just being replayed over and over again in their heads during those nights. Every single one.

I would say things like, “MRS. SMITH, I KNOW ITS TOUGH!”...

... and I would really know how tough it was.

How phenomenal was that?

What an honor it truly was...

How interesting life is...

But hey, that’s just how I saw it.

Sorry I yelled at you earlier, Old Heart. I guess that you taught me a lot over the last few weeks.

To end this post, just remember …

…. keep ya head up.